The Indo-European Similarities Project

A measure of lexical variation between different Indo-European branches and languages

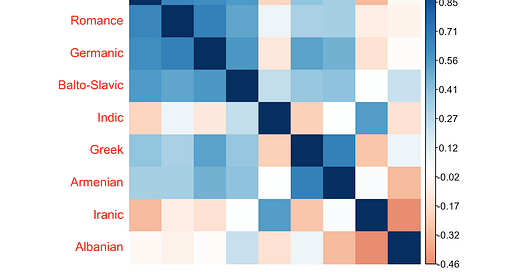

The Indo-European language family is the largest group of languages on the planet, with English, French, Russian, Greek, and Hindi all included in its ranks. I used Dyen et al.’s (1992) dataset of lexical distances between 82 Indo-European languages to investigate how similar the vocabularies of the different branches (major groups) of languages are. The chart above groups those languages according to genetic branches and calculates the average similarities between the different languages within them; linguists classify languages with the same phylogenetic method biologists use to classify species, with group and individual relationships defined by proximity to a common ancestor. In contrast, my project compares how similar their common words are. Similarity here just means how alike common words are between languages or branches, analogous to looking for similar traits between animals. If two languages are equidistant in phylogenetic sense the lexical similarity between them will be mediated by cultural contact. The words come from a Swadesh list, a list universal words like “face” and “water” that all languages share making interlingual comparisons more manageable.

European branches are generally more similar to each other than they are to Asian branches, despite being no more closely related. Close cultural contact between speakers of the various the European languages has led them to have a relative affinity for each other; Greek is as closely related to to Indic languages like Hindi as it is to Germanic languages like English, but borrowing has led the two languages to share much more vocabulary. An intriguing exception is Albanian, which bears little affinity for the other European branches aside from immediate neighbors Balto-Slavic and Greek. This suggests that Albanian speakers were somewhat more isolated from from mainstream European culture in the past than speakers of the other branches listed here. The affinity between Indic and Iranic can be explained by a genetic relationship, as the two are subunits of a common Indo-Iranian branch. Separating the two provides an easy test to see if the code I wrote actually worked; if the two didn’t show some kind of special relationship it would be clear the model was off.

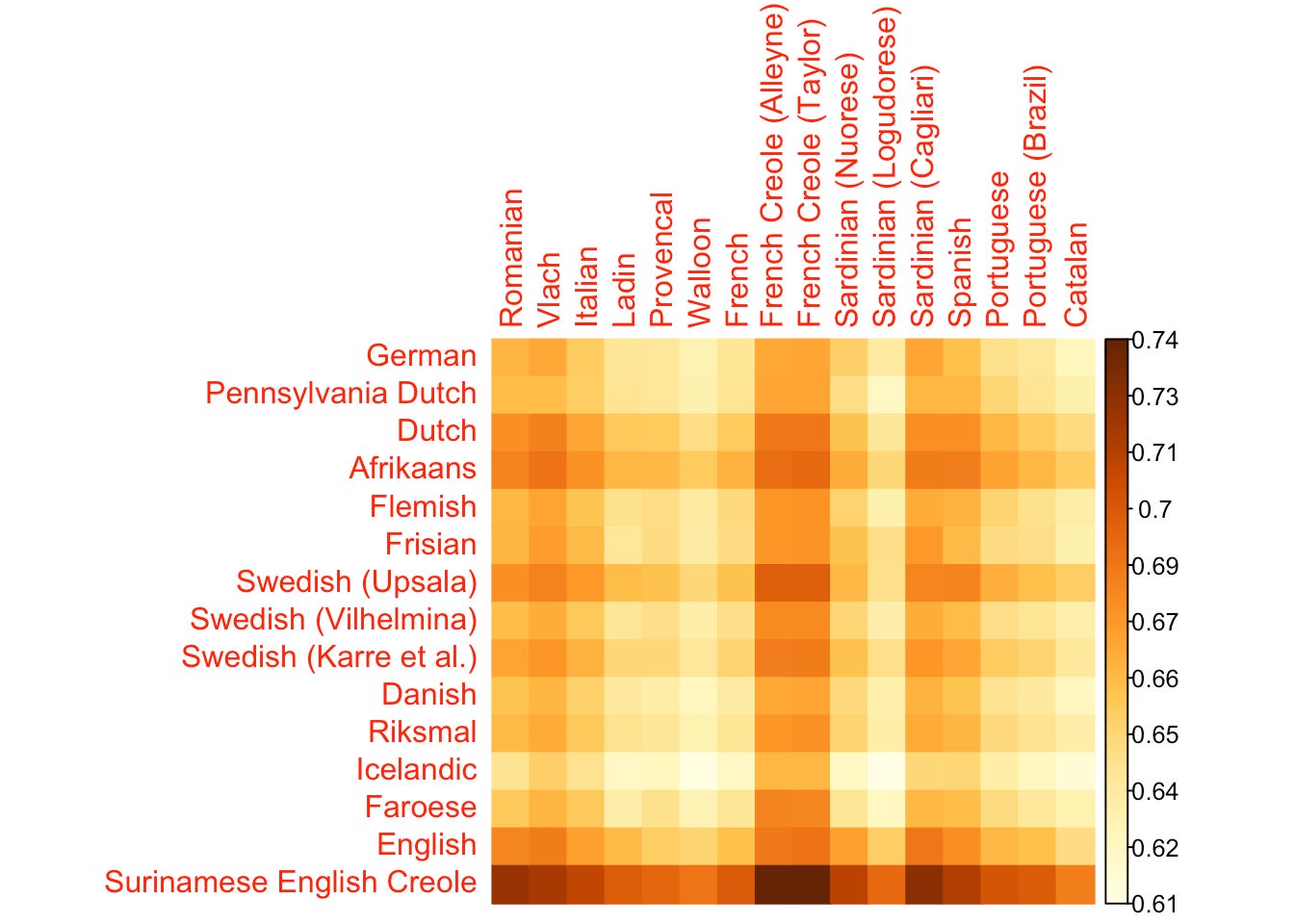

You can see from the bar on the right that there is much less variation between these two branches than there was between all of the branches on the first graph. I was surprised that English wasn’t especially similar to French (everyone’s seen a Youtube video about Norman influence on the English language by now). The two French creole languages are actually only one language, Dominican creole (from the island of Dominica, not the Dominican Republic) which is represented by two different word sets taken from two different authors; that the two are basically identical is a good sign that I haven’t messed anything up. The dialects of Sardinian match less than I would have expected, while the creole languages (formed from a mix of several different languages in colonial settings) have close affinities with everything.

Icelandic, which has changed little since the days of the sagas, has borrowed less from the Latin-derived tongues. Pennsylvania Dutch is a dialect of German spoken in parts of the eastern and central United States, and is closely associated with the Amish. Riksmal is a written form of Norwegian, but not a dialect in itself.

I wanted to compare Celtic and Indic because they are the two most distant branches, at least in geographic terms. The results are pretty strange; I would have expected a relatively close affinity between Romani and any group of European languages because, although Indic, it has been spoken in Europe by the Romani people for centuries. But why the strong links across the board to one Nepali wordset but not the other? The restriction in range to a fairly narrow window of mild dissimilarity might render the data less useful.

Note that when a language is followed by a surname it is in reference to a specific wordset, typically to distinguish it from a different wordset of the same language. The wordsets may be from the same dialect or different dialects.

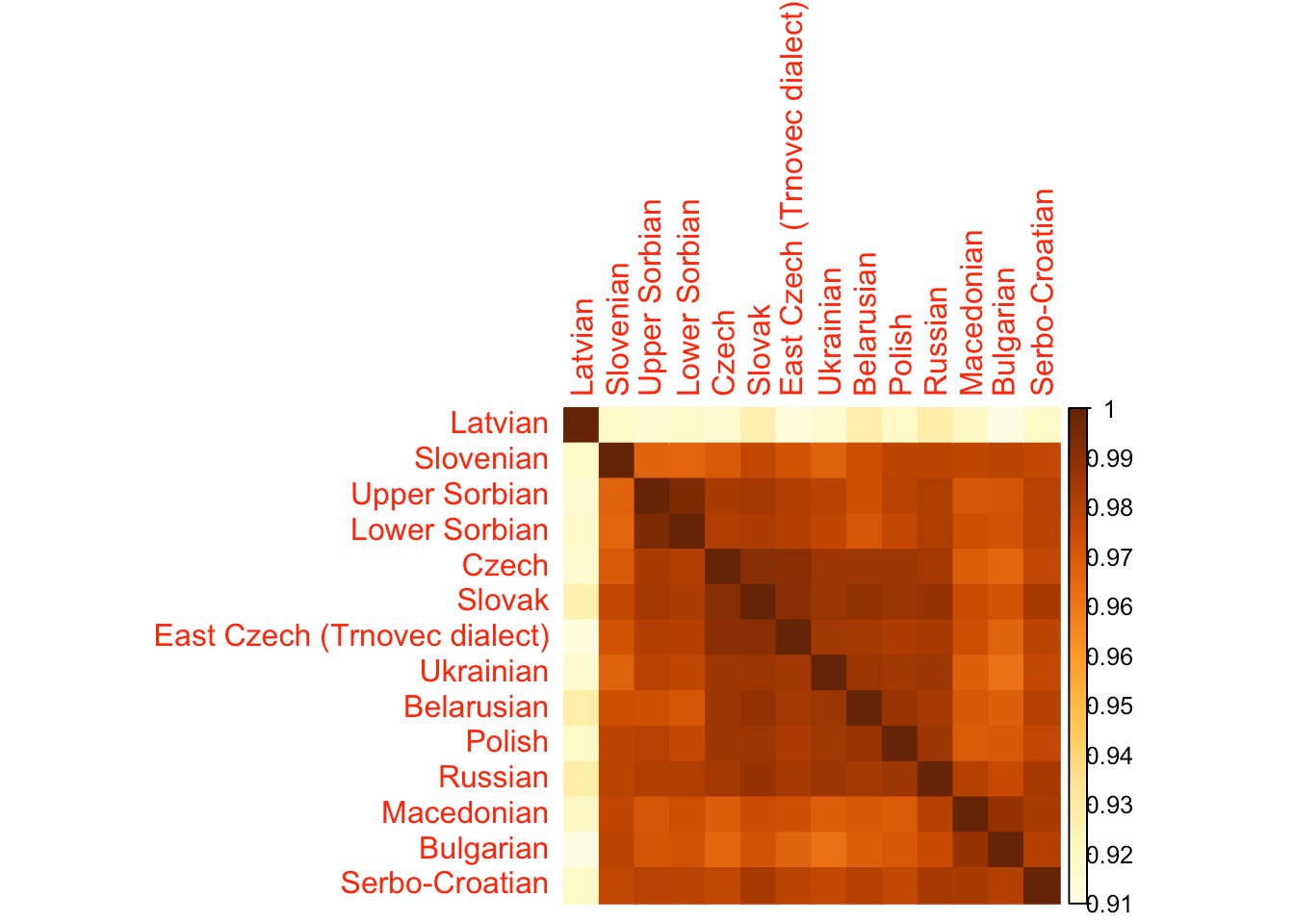

This is an internal comparison of the Balto-Slavic branch, the most politically fraught of the bunch. “Serbo-Croatian” represents most of the dialects spoken in the former Yugoslavia, which are mutually intelligible (the usual test of whether two dialects constitute a single language) but which the region’s governments insist are actually separate Serbian, Bosnian, Croatian, and Montenegrin languages. Some Lithuanians and Latvians may resent being grouped in with the Slavic languages, associated particularly with Pan-Slavist heimat and former occupier Russia, but the linguistic case here is closed. Note that Polish and Slovene are just as Slavic as Russian is.

The languages are all very similar to each other as you can see on the bar to the right of the chart, but Latvian stands out as the most distinct. This is almost certainly because Balto-Slavic is divided into two sub-branches, Baltic and Slavic, with Latvian the only representative of the former in this dataset. Other than this the range is so restricted that I don’t think the data can provide many insights.

The interbranch matrix at the top of this page came out well, but some of the more granular comparisons I made suffered from range restriction. The closer the branches or languages are the more sampling errors will skew the results because the wordsets will always be imperfect. I didn’t upload a chart comparing all 82 languages to each other because it would have nearly 7,000 individual squares, rendering the matrix unreadable.

Source:

Dyen, I., Kruskal, J., and Black, P. (1992). An indoeuropean classification: A lexicostatistical experiment. Transactions of the American Philosophical Society. 82, (5).

I made these charts in R. To find out more about the project and how you can access this data click on this link: https://dfionncurtin.quarto.pub/language-project/Source.html

Brilliant presentation too!

Fascinating stuff! Thanks for sharing this.